In July, the Bavarian State Office for Data Protection Supervision (BayLDA) published its Activity report for the year 2020 (annual reporting pursuant to Art. 59 GDPR). In this report, the BayLDA provides information on the number of complaints, consultations and notifications as well as its opinion on individual topics. Individual references (selection) can be found below:

Complaints, consultations and notifications

The number of complaints and control requests continued to grow in the fourth year under the GDPR, although not as strongly as in the previous year.

The number of consultations has fallen in relation to the previous year. This can be explained by the continuous expansion of the BayDLA’s online information, including on current topics such as the pandemic.

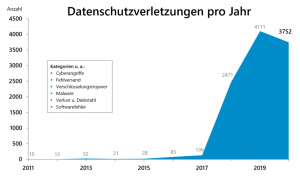

The number of data privacy breach notifications decreased slightly compared to the previous year, but remains at a high level.

Coronavirus pandemic

The collection of contact data by private individuals requires a legal basis under data protection law in accordance with Art. 6 of the GDPR. At first glance, this appears to be unproblematic, as the private individuals concerned are legally obliged to collect data (Art. 6 (1) (c) GDPR). However, this legal obligation can change constantly – like other measures to combat the pandemic. If a legal obligation is removed, there is no legal basis. In any case, the BayLDA does not accept public interests as an alternative legal basis (Art. 6 (1) (e)) (p. 19):

In the meantime, the practice of competition and training in recreational sports was also permitted to a certain extent in 2020, although contact data collection was not mandatory, but only subject to the requirement that persons with typical COVID-19 disease symptoms were to be denied access to sports facilities. In such and other cases in which the collection of contact data was or is not legally required, it must not take place because there is no legal basis for this under data protection law. If there is no explicit legal obligation to collect contact data, this cannot be based on Article 6 (1) (e) of the GDPR, because in the absence of an explicit legal obligation, it cannot be assumed that the collection takes place in the context of the performance of a task in the public interest.

On the subject of access controls, the BayLDA reminds us of proportionality and, in particular, suitability (p. 20):

One company wanted to require customers to show the Corona warning app as part of access control. We also assessed this as inadmissible under data protection law. The app only displayed “risk encounters” (in the reporting period), but this information does not provide sufficient evidence of infection with SARS-CoV2, so that the processing of this information can no more be considered “necessary” in the sense of the company’s legitimate interests [than taking a temperature using a thermometer or thermal imaging cameras].

Furthermore, the BayLDA refers to the Orientation guide “Video conferencing systems of the Conference of Federal and State Data Protection Authorities (DSK) and to the “Checklist on data protection regulations for home offices”. of the BayLDA (we have reports).

Google Analytics

As already mentioned in the last activity report (we have reports), the BayLDA reprimands the activation of Google Analytics on websites even before active consent is given. The Decision of the DSK on the use of Google Analytics further clarify that the shortening of the IP address by adding the function “_anonymizeIp()” to the tracking code is merely a security measure and does not result in the complete data processing being anonymized.

Apple camera rides

Due to Apple’s branch office in Munich, the BayLDA is responsible for Apple camera drives carried out in Germany. It assesses these according to the Decision of the DSK on prior objections to (Google) StreetView and comparable services.

The BayLDA has apparently urged Apple to provide not only a contact option on the Internet, but also by mail (p. 29):

It must be possible to file the request for non-disclosure pursuant to Article 17 (1) of the GDPR and the objection pursuant to Article 21 of the GDPR both online and by mail. These rights must be explicitly pointed out.

Schrems-II

The BayLDA emphasizes that the conclusion of the new standard contractual clauses does not provide a “simple solution” to the problem identified by the ECJ in the Schrems II ruling (RS C‑311/18 of 16.07.2020). The data exporter must actually comply with the verification obligation set out in the clauses. It must check whether authorities of the third country could possibly access the data to an extent that goes beyond what is acceptable under EU law. Here, the BayLDA envisages the following procedure (p. 47):

We expect companies and other entities that transfer personal data to third countries to conduct and document the above review. We have already received a number of complaints about transfers to third countries, and we are obliged to investigate each of these complaints. We then require the data exporter to provide evidence of the audit, in particular of the access possibilities of the authorities in the third country, and that the data enjoys a level of protection comparable to the EU level of protection, even in view of these access possibilities. If the company cannot prove this, we are generally obliged to prohibit the transfer – unless the company waives this of its own accord.

Disclosure of tenant contact data

In the area of tenant data protection, the BayLDA provides a good example of the fact that it is not always necessary to choose the milder means of achieving the purpose, but only if this milder means is equally suitable for achieving the purpose (p. 64):

[The disclosure of a tenant’s contact data by a landlord to a craftsman] is, at least as a rule, also permissible without the tenant’s consent on the basis of Article 6 (1) (f) of the GDPR because it is in the landlord’s legitimate interest that the craftsman contacts the tenant in order to arrange a repair appointment. It would also be conceivable that the tradesman exclusively gives the landlord one or more suitable dates from his point of view, and the landlord tries to coordinate these with the tenant and then gives the tradesman corresponding feedback. Experience shows, however, that it is often not easy to coordinate dates without being in direct contact with each other. Therefore, from our point of view, it is basically legitimate for the landlord to enable direct contact by passing on the telephone number to the tradesman.